In the last episode, we discussed the greatest breakthrough in ancient Greek art: the birth of the contrapposto technique. Today, we will explore how to understand the achievements of sculptural art during the ancient Greek period through specific works, along with five representative sculptures you must know. They are: “Discobolus” (The Discus Thrower), “Doryphoros” (The Spear Bearer), “The Three Fates,” “Aphrodite,” and “The Resting Heracles.”

Achievements of Sculptural Art in Ancient Greece

- Ancient Greek art was rich and diverse, with literature, painting, and even drama flourishing. Even places relatively far from ancient Greek cities, like Sicily in Italy, have remnants of ancient Greek theaters, indicating that art experienced comprehensive development during this period, with sculptural art having the most profound impact on later generations.

- Ancient Greece was not a single nation but a federation, with Athens being the most developed and civilized city-state. When we refer to ancient Greek sculptural art, we mainly mean the works that originated in Athens. The sculptural art of ancient Greece, represented by Athens, can be broadly divided into three developmental periods, reflecting a gradual progression.

- The first developmental period of ancient Greek sculptural art is called the Classical period, marked by the famous Greco-Persian Wars, roughly from 480 BC to 430 BC. After achieving victory in battles against Persia, Athens rapidly rose to prominence as a democratic, free, and advanced city-state, leading to a flourishing of art.

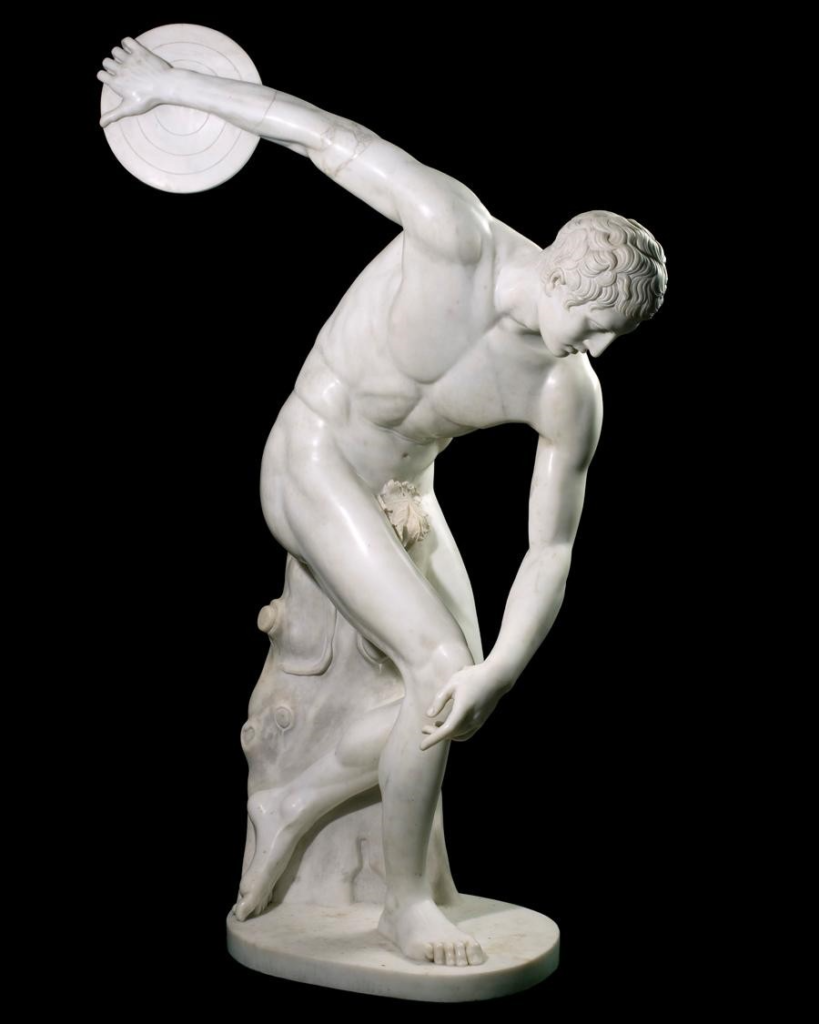

- The realism in Athenian sculptural art during the Classical period reached a high level, with Myron’s “Discobolus” being the most representative sculpture. This piece has shaped humanity’s memory of marble sculpture. Compared to earlier works, this sculpture showcases highly realistic proportions, muscular lines, and lifelike figures, depicting a man poised to unleash his strength, illustrating that ancient Greek sculptors could capture the moment of action.

- Two thousand years later, during the Baroque period, the sculptor Bernini created a work titled “David.” Compared to Myron’s piece, Bernini’s sculpting techniques were more advanced, yet Myron’s work exhibits no major flaws in realism. This demonstrates that ancient Greek sculptural art had already reached a sophisticated level during the Classical period.

- As ancient Greek sculptural art entered its high classical period, the meticulous observation of figures peaked. Sculptors of this time could easily and accurately capture the forms of their subjects. For example, the famous sculpture “Doryphoros” presents a figure that appears to be in a casual standing pose, yet all weight is balanced on one leg, representing the only correct relaxed posture in that state. This indicates that artists of this period had achieved a very thorough understanding of human form.

- By the late Classical period, ancient Greek sculptors became bolder and were no longer content with merely depicting nature and human figures; they began to define aesthetics. Sculptural works from this period created a variety of bodily forms, with many elements influencing modern aesthetic concepts.

- A notable sculptor from the transition between the high and late classical periods is Phidias (Pheidias), who held a crucial position in sculptural art during this time. His significant work, “The Three Fates,” remains remarkable, and although parts like the head and hands are now incomplete, the precise depiction of human postures is still evident.

- “The Three Fates” by Phidias may initially seem unusual, as its overall center of gravity tilts to one side. In fact, this sculpture was originally placed on the sloped roof of a temple, so considering its original environment, it appears very elegant and fitting.

- Praxiteles is another crucial sculptor of this period, known for defining the “Praxiteles curve.” The modern aesthetic appreciation of the female S-curve stems from his work. His famous sculpture “Aphrodite” is the first renowned nude female sculpture in ancient art, originally carved for the ancient Greek city of Kos, which later could not accept the nude form. Consequently, the city of Knidos embraced this statue, placing it in a temple, showcasing the female form in an S-curve.

- Lysippus was the official sculptor for Alexander the Great and introduced the concept of the “nine-head” human proportion. His representative work, “The Resting Heracles,” features a figure whose height is nine times the length of his head, creating a very athletic and harmonious appearance.

- To depict the strength of Heracles, the sculptor Lysippus chose not to portray the hero in an overtly powerful pose, but rather allowed him to lean against his spoils. Even in a resting position, he exudes a sense of power, subtly illustrating his immense strength.

Myron – “Discobolus” (The Discus Thrower), with copies currently held at the National Museum of Rome, the Terme Museum, and the Vatican Museums.

Bernini – “David.”

Polykleitos – “Doryphoros” (The Spear Bearer), currently housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples, Italy.

Parthenon.

Phidias – “The Three Fates,” currently held at the British Museum in London.

Praxiteles – “Aphrodite,” showcasing the female form in an S-curve.

Lysippus – “The Resting Heracles,” currently housed in the National Gallery of Capodimonte in Naples, Italy.

How to Appreciate a Sculpture?

While the primary goal of appreciating art is enjoyment, understanding an artwork can be subjective and personal. When appreciating a sculpture, avoid focusing too much on aesthetic motivations alone. Start by learning the background of the piece—what story it tells, what character traits the figure embodies. Then, bring these narrative elements into your experience as you view the sculpture. This approach allows you to imagine the story, bringing the sculpture to life before you.